What is the value of a Bitcoin miner?

On my personal journey to understand Bitcoin, I made my share of mistakes. A lot of people got involved in broad crypto-trading and suffered significant financial losses. While this essay is not an economic assessment of what we affectionately call shitcoins, I bring it up to say that I turned out to be in the great minority of people who never dabbled or were ever interested in it. I don't say that necessarily as a flex, but I do think it reflects my basic understanding of risk, markets, and economic value in some small way. My big mistake was in 2022 when I bought a brand new ASIC miner, a Bitmain S19JPro. ASIC (Application-Specific Integrated Circuit) miners are specialized devices designed specifically for Bitcoin mining.

I'd love to be able to express my mindset right at the moment that I pulled the trigger. I was confident, measured, and had all of 3 months of experience in Bitcoin under my belt. I chose a great company to host the machine and they were far and away a great partner, avoiding all of the horror stories others faced during 2022. And it was still a terrible mistake for one simple reason: The machine was destined to never return anywhere near the bitcoin that I could have gained just by instead buying the Bitcoin. This was true even if I had received free electricity, not to mention the excellent 6.9 cents per kWh contract I secured with my host. How did I have the sense to avoid shitcoins but still make such a poor decision to buy a machine that had no ability to pay off its purchase price? I will argue that Bitcoin mining has a way of turning smart people into bad investors from the individual level all the way up to the biggest capital allocators.

My background as an actuary and financial analyst made me naturally curious and interested in the valuation of Bitcoin miners. There are no books on how to do it, and there is very little guidance online about how people think about it. Despite no academic corpus, and no established best practices, they were widely used as collateral for many large mining operations, some of them public companies with large market capitalizations. Learning how much the mining industry was structurally tied to the value of miners was astonishing. Most companies need to go to specialized appraisers to validate the valuations of important items on their balance sheets. Core Scientific and Argo Blockchain were examples of large miners with large market caps, in the multiple billions. Each of these companies were undone by a revaluation of their equipment, which had no discipline for valuation and ended up being a proxy for the price of Bitcoin. When the miners were revalued at pennies on the dollar, the collateral value crashed and they faced liquidation. The companies had to file for bankruptcy to delay the liquidation of the miners, which would have eliminated their primary revenue source. Brought to the brink of disaster over poor risk management and lending practices, I began to feel less stupid about buying my miner. So what is the value of a Bitcoin miner? As the Austrians love to tell us, value is subjective and this industry is no different.

Mining Bitcoin is Irrational

Mining is primarily irrational from an economic perspective. The majority of people engaged in it are doing so apparently at a USD loss today. Ask them why they do it and they'll give you all kinds of answers like heating their houses, heating their pools, drying their clothes, or just mostly curious about how it all works. At the end of the day, a large amount people engage in mining simply because it's ungovernable and they want to stick it to the man. Few people are in it for the profit. That's irrational from a capital markets perspective.

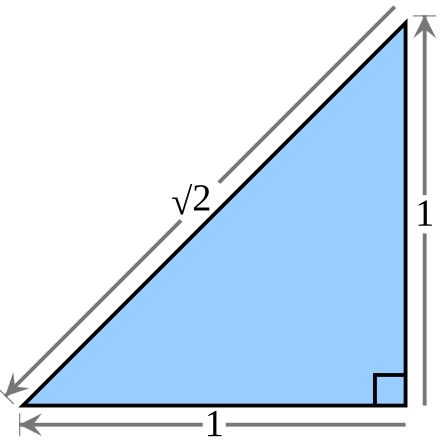

To put context around the words "rational" and "irrational", I'll go to my favorite source of wisdom: mathematics and number systems. There is a number system called integers (we know and love them as whole numbers) that consists of every such number e.g. (..., -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, ...). We sometimes call these the counting numbers, even though negative numbers don't make a lot of sense from a counting perspective. The negatives were invented to allow every counting number a way to add to zero (the additive identity). One day, someone wanted to extend this idea to multiplication and be able to multiply a number to an integer to get 1, and realized that he couldn't do it without fractions - so they invented something called the "Rational number system". The rational number system consists of any number that can be expressed as a fraction of 2 integers (p/q, where p & q are integers, and q is not 0). Examples of these rational numbers are 1/2 and 5/8.

If that is rational, than how does one define irrational? The irrational number system refers to numbers that just cannot be rational. The most famous example is the square root of 2, which is clearly an actual number (part of the "real" number system) - as can be seen if one draws an isosceles right triangle with lengths 1. Thanks to the Pythagorean theorem, we know that the length of the 3rd side (aka the hypotenuse) is the square root of 2. But this cannot be expressed as an integer or a fraction consisting of integers.

https://en.wikipedia.org//wiki/Square_root_of_2

Ironically, Pythagorus never knew what an irrational number was. He spent his entire illustrious life believing every number could be expressed as a fraction of integers. This was even despite one of his own students, Hippasus, discovering the groundbreaking proof that sqrt(2) cannot possibly be rational. Other Pythagorean loyalists decided that the truth that Hippasus discovered cannot be known to the public and they murdered Hippasus while entering a pact to never publish the proof. The effort obviously failed, since Hippasus proof ended up being among the most famous proofs in the history of mathematics. Proofs are ungovernable and so is being irrational, and this is really the only way I can explain those who choose to dedicate resources to bitcoin mining. Ungovernable, and irrational.

Is It Worth It?

I'd like to first express the purpose of this analysis to begin with, which is to give a sense of what a miner is capable of earning for its owner. The owner is subject to variables like their cost of electricity and their skill as a host in keeping the workers operational, but its useful to see what the miners would be capable within a simplified world of constraints to evaluate whether or not purchasing a miner has economic benefit to them. I'll start out with some basic assumptions so a miner can simply gauge what they might earn. In addition, you might wonder why certain assumptions are omitted from the analysis that would have a material impact on the valuation of a miner. For example, miner uptime can significantly impact the revenues expected of an ASIC. Assumptions such as these are explicitly removed to maintain a simple framework for answering the basic question: "Is this miner going to pay off more satoshis than if I were to just buy the Bitcoin peer-to-peer or on exchange?" If the answer is no in an overwhelming number of scenarios, which I will show to be the case, improving uptime isn't going to be a significant lever to change that fact. The key assumptions I included, namely expected difficulty adjustment, expected fees, and per-kilowatt-hour-cost are ones where a reasonable deviation can make that difference.

Aside from the expectations about assumptions, the analysis assumed an expectation for the smoothness of satoshi revenue. In reality, a miner will win a block within a reasonable expectation of the hash it puts towards doing so but the frequency of its payouts will be highly irregular and unpredictable. Mining pools offer several payout structures but the most popular is called FPPS (Full Pay Per Share) https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Comparison_of_mining_pools - this structure essentially pays our proportionally to a miner's relative contribution of hash rate to the network. In an idealized world, enough pooled miners could leverage the "Law of Large Numbers" and be paid per block this way according to the FPPS structure. Without opining on the qualities of the structure and what it means for the industry, I kept the math simple in the model by assuming that each miner would be paid according to an FPPS-like structure where each block they would receive a relative proportion of the block reward and fees according to its contribution of hash rate to the network.

What is it Worth?

Now how should one approach the question of the value of a Bitcoin miner? A few first principles come to mind. The upper bound value of a miner is the amount of satoshis it can yield if the user has free access to electricity, and the lower bound value is what a user can sell its parts for.

- Breakeven: The machine should, at a minimum, return the amount of satoshis that you spent on it. Said another way, you should be indifferent from a return perspective about buying the bitcoin versus using the miner to acquire the Bitcoin. In reality, you should not be indifferent because when you buy Bitcoin, you get it immediately with no additional risks like difficulty adjustments, curtailments, outages, etc. The machine should actually return a premium to compensate for these additional risks to acquire the bitcoin. What should that premium be? That would be subjective and left to the buyer. In my suggested valuation framework, we will make reasonable assumptions for these things to keep the decision simple.

- Difficulty assumption: this is unironically difficult to build into a model but its important to understand the essential inflation drag a miner is constantly under. As difficulty increases, a miner contributes less hash relative to the overall network and thus earns less rewards over time. To assume that this is zero would be a grave error. Historically, the difficulty lowers in the first year of the epoch after the halving, but increases about 30% per year in the other three years.

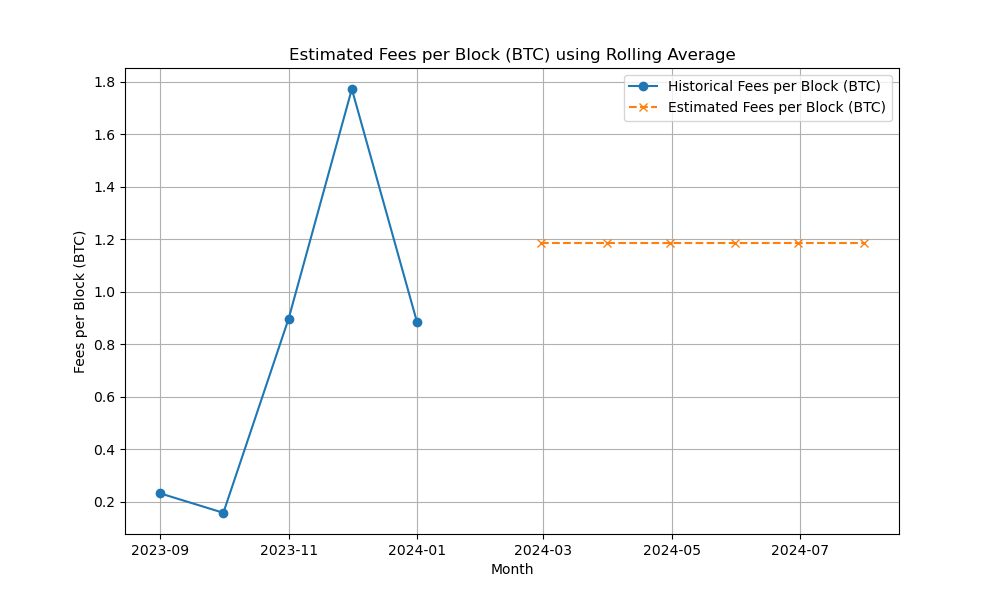

- Fee income: Fees were all over the place in 2023, with periods of time exceeding the 6.25 btc block reward itself to very sparse times where you could still transact for 1 sat/vbyte. Rather than assuming that the fees would be significantly high or low forever, I looked at the average over the past year and assumed an income of half of that.

- Cost of electricity: this may be the most controversial input assumption because most sellers don't care how much their buyers are paying for electricity. It shouldn't objectively impact the value of the asset should it? The asset has intrinsic value (parts can be sold) and that is certainly independent of a buyer's electricity costs. However, in the context of providing breakeven value, how could this be ignored? The hard truth of the Bitcoin protocol is that if your buyer can't access electricity at under 6cents per kwh, then there is practically no mining machine capable of breaking even

- Intrinsic Value: A miner, no matter how many (or how few) satoshis it is capable of yielding its owner has an intrinsic value that consists of the parts that can be sold off of it. This isn't necessarily easy to estimate but products like the Bitaxe have demonstrated an aftermarket for miner parts, particularly the hash boards. As a lower bound for the price of a miner, I'd suggest looking at the price of a higher end Bitaxe. At the time of this writing, they sell for $300. This will be what I use as a lower bound for a miner's price

With these first principles in mind, I set out to value a few miners knowing how much electricity they consume every 10 minute block. On the revenue side, it's easy to know how much Bitcoin a miner will earn each block (on average), though as a more advanced topic, I'd argue that there's an unrecognized cost to using FPPS which is the capital base of the pool providing the smooth returns. For simplicity of discussion, I'll assume that the bitcoin revenue is a direct proportion of a miner's hash relative to the network. As of writing, the Bitcoin network’s total computational power, or hash rate, is around 600 exahashes per second (EH/s), which indicates the enormous scale of mining globally..

In General, You're Miners are Unprofitable

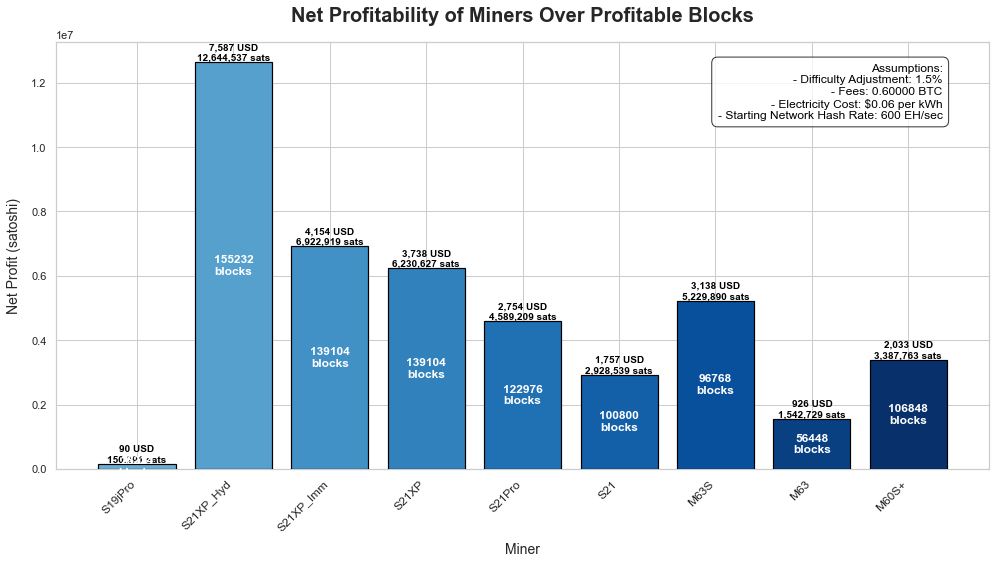

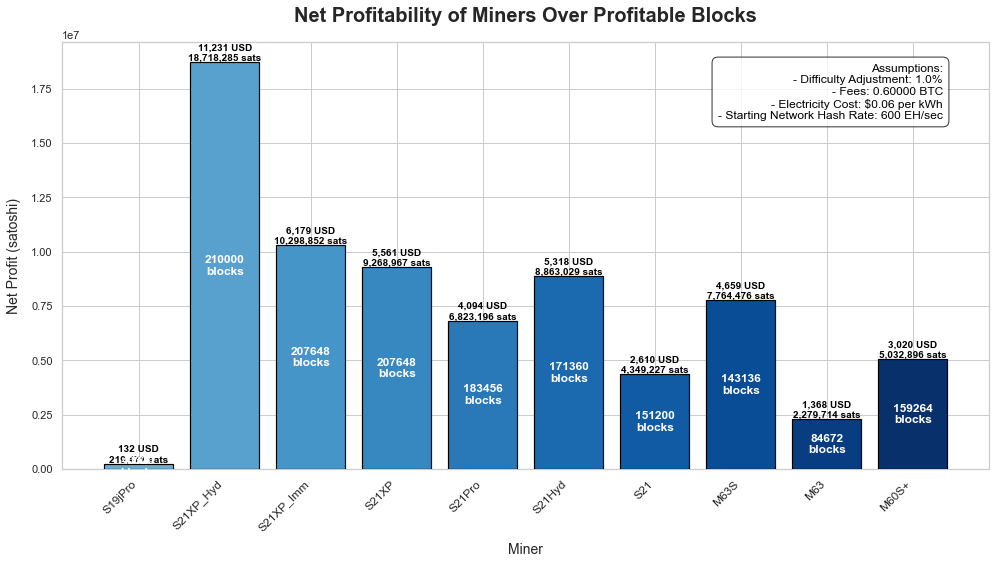

The first chart shows the net revenue that a range of miners will produce under the following assumptions: 1) the difficulty adjustment is a constant 1.5% per 2016 blocks. This may seem extreme and arbitrary but it translates to about a 40% increase after a year, which is on the conservative end of historical; 2) the host spends 6c per kilowatt hour on power and that cost is constant (say, via a power contract); 3) Fees awarded at a rate 0f 0.6 bitcoin per block (which is about half of the average over the past year)

The next chart shows the same data but with a difficulty adjustment assumption of 1% per 2016 blocks, which translates to 30% annual, still quite reasonable. The increase in profitable blocks and breakeven values over the 1.5% assumption is apparent.

The first insight I would glean from the profitibality chart is seemingly obvious: most Bitcoin ASIC miners are priced well beyond their breakeven value. Older machines like the S19jpro are essentially worthless from a value perspective, and while the parts carry some value, my expectation is that an insignificant portion of the buying market is buying S19s to resell the parts.

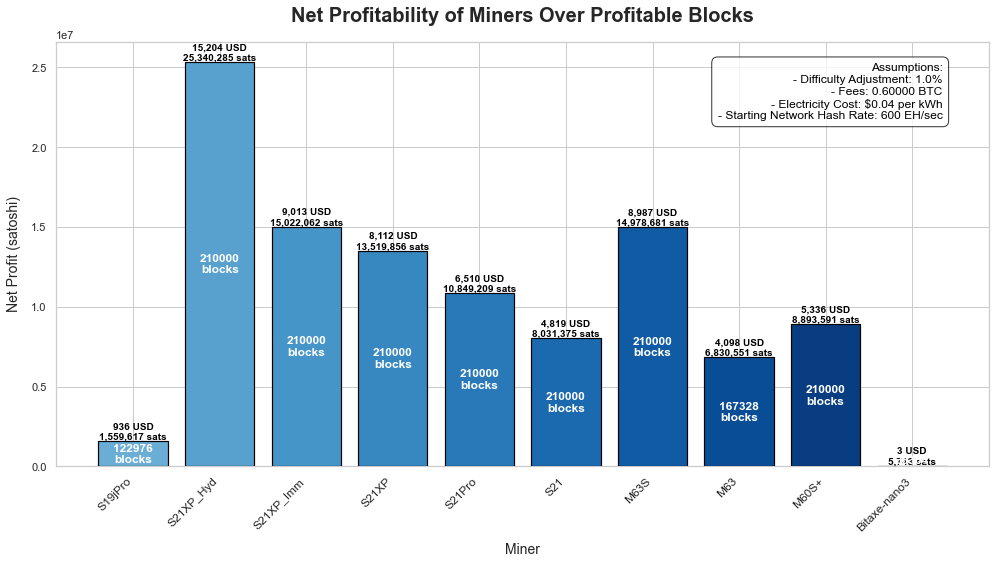

Finally, we show the same data with a 1% difficulty adjustment, but for someone paying 4c per kilowatt hour for electricity

If you can lower your electricity costs to 4c/kwh, you start to see miners pay off beyond breakeven. The S21 Pro, which sells for $5k, will pay off well above that (30%) but not if the difficulty is more severe than 1% per 2016 blocks. Additionally, it requires 4c/kwh to make the new Bitaxe Nano3 worth turning on for 38,000 blocks to earn $3, a far cry from the $300 you will pay for it.

Bitcoin Miners are Irrationally Priced

The price signal in the Bitcoin ASIC market is extremely irrational. Buyers generally don't understand what they are buying. But even more interesting, sellers don't seem to understand what they are selling and lenders don't understand what they underwrote as collateral. It seems a little bit better this cycle (the industry isn't using ASIC's as collateral nearly to the extent that it had prior to 2022) but the data I presented tells a highly irrational story. The majority of the industry's inventory is priced far beyond its breakeven value. There are only three possible conclusions I can definitively make in general: 1) Buyers of miners are willing to pay far more for less Bitcoin than they can otherwise buy it for from the open market; 2) Buyers of miners are willing to pay large premiums of money and time in order to get "virgin" Bitcoin straight from the protocol; 3) Buyers of miners are motivated by a ASIC's value that is significantly different from just earning Bitcoin (perhaps its social, or a sense of virtue) and are willing to pay a large premium for it.

The good news is that fortunes are made in irrational markets, not rational ones. Armed with good information, one might succeed as buyer or a seller. In the land of the blind, the man with one eye is king. It is very likely that the winners in this game are those who 1) earn enough Bitcoin outside of mining to hold in reserves; and 2) can effectively deploy their Bitcoin to ongoingly lower their fixed USD costs, for this seems to be the only real path to rational mining returns. In future analyses, I’ll explore strategies where miners can leverage their Bitcoin reserves to reduce operational costs, potentially transforming the economics of mining. Stay tuned.